Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Brash ‘Bad Boy’ Bill Johnson showed Americans how to win in Euro-centric sport

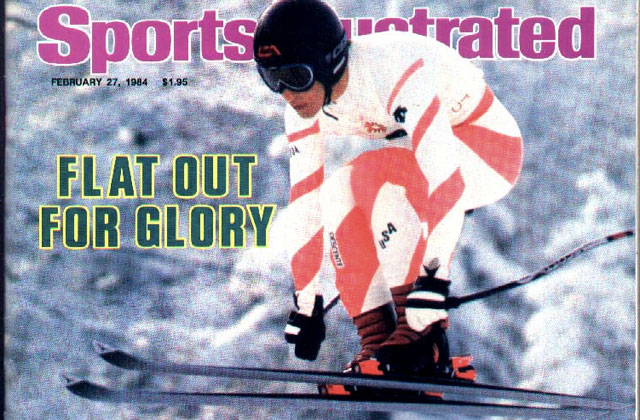

Bill Johnson, America’s first ever men’s downhill Olympic champion, won at Aspen in 1984, 13 years before the debut of Beaver Creek’s Birds of Prey course (Sports Illustrated cover).

“Bad Boy” Billy Johnson, as much as any other ski racer, set the tone for how Americans had to make their mark in a European-dominated sport. His death at age 55, right before the Super Bowl of ski racing this weekend on the Hahnenkamm at Kitzbuhel, Austria, ends a tragic tale of triumph, a terrible fall from glory and an unfulfilled quest for redemption.

Johnson, ski racing’s Joe Namath, called his own shot and predicted victory over Austrian legend Franz Klammer and a stacked field in the Olympic downhill in Sarajevo in 1984. Then he delivered what no American man had ever accomplished up to that point: the first ever gold medal in downhill and, in fact, men’s alpine ski racing in general.

As Ski Racing Magazine’s Hank McKee points out, “Johnson’s legacy is in concrete. As he told Sports Illustrated’s great writer William Oscar Johnson in 1985, ‘I made it to the top, and I was the first to do it. No one can take that away — ever.’”

William Oscar Johnson is the late father of Vail Valley local TJ Johnson, grandfather of youngest ever U.S. Ski Team freestyle team member Tess Johnson, and also the man who penned Vail founder Pete Seibert’s book “Vail: Triumph of a Dream.”

As far as Bill Johnson goes, no ski-racing fan from that era will ever forget his brash style that so enraged the Euros and set the tone for iconoclastic Yanks for decades to come, from Picabo Street to Bode Miller.

That style rubbed his own European coaches the wrong way on the U.S. Ski Team, incredibly costing him a place on the 1988 Olympic team in Calgary, Alberta – to date the worst showing ever by an American alpine squad after its best-ever showing at Sarajevo in 1984.

As former U.S. Ski Team member, Colorado Ski and Snowboard Hall of Famer and lifelong Vail local Mike Brown points out, that rift cost Johnson and many other racers a shot at Olympic competition in a lost decade for the team after such dominance in 1984

Brown blames that travesty on former USSA chief Bill Marolt for not overruling his coaches, in particular head U.S. Ski Team coach Teo Nadig of Switzerland.

“If you look at how we were treated as a team, Teo Nadig absolutely despised Americans, so it’s kind of ironic that he was coaching the American team,” Brown told me a couple of years ago. “Bill Johnson, all of that stuff where he was at odds with the team, that all came from Teo Nadig, and there was absolutely no reason for Bill to be treated as an outsider.”

Johnson also won a World Cup downhill at Aspen the same year he grabbed that first Olympic gold in Sarajevo, and he forever changed expectations for U.S. men in the White Circus. He laid the groundwork and set the tone for Tommy Moe, Daron Rahlves, Bode Miller, Ted Ligety and all the other American greats – current and future – who have won a World Cup race.

Here’s a press release from the U.S. Ski Team about Bill Johnson’s death:

GRESHAM, OR (Jan. 21, 2016) – Olympic champion Bill Johnson, whose storybook 1984 season ushered in a new era for American ski racing, passed away Thursday at an assisted living facility outside Portland at the age of 55. His passing closed the final chapter in a tumultuous lifetime that saw him rise to the highest level in his sport.

Born in Los Angeles, Johnson grew up ski racing at Bogus Basin in Idaho, then moving on to Mt. Hood in Oregon as well as the racing program at Mission Ridge, WA.

At the age of 23, Johnson burst onto the World Cup scene in 1984, winning the storied Lauberhorn downhill in Wengen. It was the first American men’s World Cup downhill victory in the modern era. The next month, he backed it up with an Olympic gold in Sarajevo, then closed the season with wins in Whistler, BC and Aspen, CO.

He retired from competition in the late ‘80s after a series of injuries and personal setbacks. But with the impending 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City, he staged a comeback. On March 22, 2001, he was critically injured in a crash at The Big Mountain near Whitefish, MT during the U.S. Alpine Championships. Near death, he remained in a coma for three weeks before regaining consciousness. While he did ski again after the accident, his racing career was over. In recent years, medical complications increased and he was confined to an assisted living facility.

Last March, on his 55th birthday, friends and ski racers around the world reached out with tributes to one of the greatest downhillers of all time.

Johnson’s Olympic gold punctuated a stellar Olympics for the U.S. Alpine Ski Team in Sarajevo, winning five medals including gold from Johnson and Phil Mahre. His accomplishments motivated an entire generation of American ski racers, with the team’s current success rooted in the achievements of that 1984 Olympic Team.

Details on any services for Bill Johnson are pending.