Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

How housing, public transportation and health care are so inextricably linked

I have a long history of advocating for higher-density, in-fill, subsidized and deed-restricted workforce and middle-class housing throughout the Vail Valley, so I’m not about to rail against a dorm-style project approved at the entrance to my neighborhood in EagleVail.

I also have a long history of saying we don’t have a parking problem in Vail, we have a car problem. Those two things – affordable housing and public transportation – go together like President Donald Trump and lying. You can’t have one without the other.

For that reason, the proposed Booth Heights workforce housing project, which on Monday received a 4-3 thumbs up from the Vail Planning & Environmental Commission is in exactly the right place – along Interstate 70 and North Frontage Road with a nearby bus stop.

It’s now up to outraged East Vail residents to prove they really opposed the project because of potential impacts to bighorn sheep habitat and hold the town, Vail Resorts, Colorado Parks and Wildlife and the U.S. Forest Service accountable for helping mitigate deadfall in the sheep habitat area – something their own opposition to controlled burns has stalled since at least 1998.

Speaking of that year, that was when ecoterrorists set fire to Two Elk Lodge and several other buildings and chairlifts on Vail Mountain in the name of the Canada lynx they said would be ravaged by Blue Sky Basin. Turns out that didn’t happen, and in fact Vail Resorts contributed to the successful reintroduction of the lynx in Colorado. Could the ski company be part of a similar success story with Vail’s bighorn sheep population?

[As a quick side note, I almost got run over by a bighorn ram while skiing up Davos Road in West Vail last winter, so the herd clearly roams all along the North Trail area. Perhaps a broader mitigation effort would increase their range and get them off the side of the interstate – unless it really is good for them to breath fumes from semis and lick mag chloride].

In my own backyard, I did not oppose the repurposing of the Warner Building at the Highway 6 and Eagle Road entrance to EagleVail but instead asked the commissioners to push the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) for a roundabout at that already badly broken intersection and to dramatically improve our inadequate ECO Transit bus system.

Imagine, for a moment, if the countywide bus system was as frequent, reliable and free as Vail’s in-town bus service. Would any locals drive into Vail, Avon or Beaver Creek again – to work, play or ski? While we’re dreaming, also imagine if all those buses were electric, further allowing us to determine what types of fuel we prefer for our electrical grid in Colorado.

We’ve already gone from a 70-percent coal-powered state to around 50 percent in just the last 12 years, with most of that coal consumption being replaced by natural gas and wind. Once renewables top natgas in our power grid and we get our reliance on Wyoming’s Powder River Basin coal down closer to zero, Colorado will have completed a remarkable transformation.

The Vail Valley (sorry but that inaccurate name is ingrained in our lexicon) needs to be a leader of that transformation by promoting in-fill, higher-density housing, penalizing irresponsible McMansion construction for absentee owners, massively taxing short-term rentals and focusing all of that money into a housing fund to work on the workforce housing shortage countywide.

Vail InDEED needs to be a countywide program with a permanent funding source, allowing locally occupied units with local workers to be deed-restricted from Dotsero to East Vail. The program is paying dividends and should have been in place and permanently funded well before the housing crash of 2008. Imagine how many distressed properties could have been locked up.

I agree with a recent Vail Daily editorial that a high-speed bullet train to the mountains is a fantasy fix for an overwhelmed Interstate 70 that will never come to fruition – chiefly because we lack the political will to tax gas at appropriate levels to fund the massive public transit projects common in Europe and Asia. So what do we do instead?

Everything in our power to reduce vehicle traffic, especially the gas-powered kind. The Colorado Department of Transportation’s Bustang service is a start, but it needs to be dramatically stepped up during peak times, with truck traffic curtailed and tolls for HOV lanes (three-plus people) from Denver to Glenwood.

And continue to aggressively electrify vehicle traffic along the corridor. Adoption by Colorado of California’s zero emission vehicle program is a positive step but how can we get commercial traffic on the same path while also compelling counties and towns to electrify their fleets?

As for commuter trains in Eagle County, it’s unfortunate we have a dormant rail line running right through Dowd Junction and all the way west toward the Eagle County Regional Airport. While a commuter line less ambitious than a bullet train may be a bit of a pipe dream as well, if the railroads would abandon that line, it would at least help connect our piecemeal trail system.

Meanwhile, stepped-up public transportation and greater housing density along the frontage roads and interstate are key. Back in 2006 I wrote that Solaris should be built even higher to screen the impacts of the interstate from Vail Village. Now try to imagine Vail without Solaris.

Ditto the Green Mile in EagleVail. The owners of all those one-story warehouses along Highway 6 should be approached for redevelopment via public-private partnerships. Leave the tire stores, body shops and dispensaries on the ground floors, but stack four, five or even six stories of prefab workforce housing on top – right on the bus route and just five minutes to Vail and Beaver Creek. It would serve as a very useful screen between I-70 and residential EagleVail.

I applaud the county for its work with CDOT on the Highway 6 road diet that will add badly needed sidewalk and a bike path, but let’s think even more outside of the box on how to properly utilize an invaluable area (including critical State Land Board land) that’s so close to our major resort attractions.

Similarly, ECO Trails needs to get the bike path finished through Avon. Trails that close in can and should be part of our overall push to get cars off the roads.

While Avon had the vision to preserve transit options with the train tracks near a new gondola when it approved the Westin Riverfront, there was a decided lack of vision in not requiring a parking structure and following through on the pedestrian mall concept connecting over to the beautifully revamped Nottingham Park and its outdoor concert venue. Avon could have had a true Village at Avon similar to Vail Village – instead of the vacant parcel with that name that’s finally showing some signs of life after 20 years.

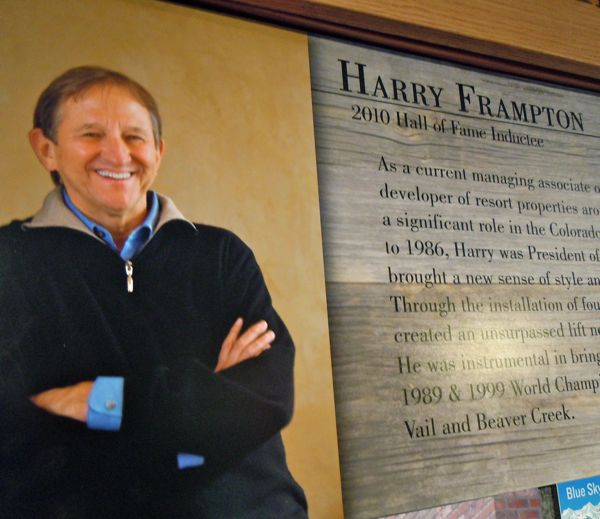

East West Partners founder Harry Frampton – the developer behind the success of Beaver Creek and the rebirth of downtown Denver — told the Colorado Sun back in May that the Village at Avon land owned by Magnus Lindholm should be purchased well above market value by the many (too many, in his mind) government jurisdictions in the Vail Valley. The public (read, your tax dollars) should then build 1,000 or more units of workforce and affordable housing.

It does appear that Lindholm is in a mood to sell (and the latest free-market apartment project there is apparently looking to take advantage of tax breaks via Avon’s 2017 Opportunity Zone designation), but I question how much of the burden should fall on taxpayers and how much should be shouldered by the business community. Public-private partnerships and innovative deed-restricted projects like Booth Heights seem more prudent to me.

I reached out to Frampton for a recent story on the intersection of the housing crisis and health care in mountain communities. It was a cover story for Colorado Politics and placed behind a pretty pricey paywall, but here’s the Frampton interview from that story, excerpted and preceded by one bonus quote that didn’t make it into the article.

Without zeroing in on specific projects, I asked Frampton where we should be building the wide range of housing types so desperately needed in the Vail Valley, from seasonal workforce to attainable middle-income units for young families. Here’s what he had to say:

“Any land we’ve got left. I don’t care. Put some in Vail, some in Avon, some in Edwards and not just move everybody to, we’ll call it to west Gypsum, right?” Frampton said, acknowledging the adverse climate-change impacts of continued sprawl and inadequate public transportation.

Now here’s the promised excerpt from the part of the story focused on Frampton:

Harry Frampton of Vail, founder of East West Partners and a group of companies that develop, sell and manage real estate across the West, sits on the board of Vail Health – the area’s largest health care provider and Eagle County’s second-largest employer.

Frampton said the scarcity of housing is definitely impacting the overall health of Vail Valley residents, prompting hospital officials to scramble for ways to bring down health care costs along with runaway health insurance premiums.

“You go through all these issues, and I’m on the hospital board and we’ve been talking about it a lot, struggling with it, and I say, ‘Well, all of this is great, but if we just paid people more, they’d do better,’” Frampton said. “They’re struggling financially because we do have a nutty cost of living.”

Frampton called on Vail Resorts, the largest employer in Eagle County and one of the largest in the state, to up its minimum wage to $15 an hour – a move that its rival, Aspen Skiing Co., recently made and one that he says East West made more than two years ago.

Broomfield-based Vail Resorts operates the Vail, Beaver Creek, Breckenridge and Keystone ski areas and has hotel and other real estate interests in those areas. Low wages, Frampton said, is one of the biggest factors impacting the overall physical and mental health of Colorado residents, especially in the Vail Valley.

“All the above. It’s one of the reasons I believe we were the first company in the Vail Valley two years ago to raise our minimum wage from 12 to 15 bucks,” Frampton said. “Part of the problem is Vail Resorts doesn’t pay enough …”

Vail Resorts raised its minimum wage to $12.25 an hour last season and has reportedly yet to set its wages for the coming ski season, but CEO Rob Katz has acknowledged the need to do better on both wages and housing.

Frampton advocates for a wide array of solutions to the housing and health care crisis, arguing there’s no single silver-bullet policy fix.

“We’ve got to pay people more and we do have to support them and have a better infrastructure in mental health,” Frampton said. “We do have to remain creative in employee housing. We do have to have a great education system. So my sense though is that if you look at Vail overall, we’re doing pretty good in the community addressing tough issues and we’re doing a lot of innovative stuff. Some will work, some won’t work.”

Frampton also cites East West’s month-long sabbatical program as one of the reasons the company in May was named the top firm among large companies in The Denver Post’s 2019 Top Workplaces contest.

Frampton, whose company developed downtown Denver’s Union Station and Riverfront Park neighborhoods, agrees that long commutes can have a negative impact on Coloradans’ health.

“Everything we do should be to discourage cars and encourage pedestrian walking and public transportation. Every decision,” Frampton said. “I understand we’re spread out, different areas, you’ve got to move back and forth. But how do we discourage traffic and cars?”

Frampton acknowledged that “not-in-my-backyard” syndrome (NIMBYism) makes it difficult to get all the various types of affordable housing built in Colorado communities – from temporary workforce rental units to for-sale middle-income housing for young families. But that doesn’t mean communities should stop trying.

“I think as a general rule, we people who’ve kind of made it, we kind of figure workforce housing is the bad people. BS. We all started in workforce housing, did we not?” Frampton said. “At some point in time, we all did. We’re talking about people who are good people. They’re our future leaders.”