Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Local Rep. Roberts backs Polis order on electric vehicles

Gov. Jared Polis last week moved to adopt California’s Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) standard, issuing an executive order that drew praise from local lawmaker Dylan Roberts of Eagle.

“This is an exciting and important step for our state and for our environment,” Roberts, a Democrat who represents both Routt and Eagle counties in the State Legislature, told RealVail.com. “I am glad to see the new governor prioritize the issue of our time and generation, climate change, in his first executive order.

“Making electric vehicles more accessible to more Coloradans will boost the ongoing transition to cleaner fuels and more efficient vehicles. This kind of action also incentivizes the modernization of our electrical grid to accommodate the increased demand for clean energy.”

Below is the Polis administration press release on the Democratic governor’s first executive order since taking the oath of office earlier this month. Polis, the former U.S. congressional representative for Colorado’s second district that includes part of Eagle County, was elected in a blue wave during the November 2018 midterms.

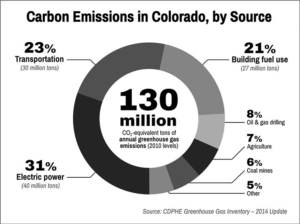

Polis ran on a platform that included the goal of powering the state with 100 percent renewable energy by the year 2040. But that just targets the electric power sector, which, according to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, accounts for 31 percent of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Transportation is second at 23 percent of the state’s emissions, according to the CDPHE’s 2014 statistics, and building fuel use comes in third at 21 percent. Ideas for mitigating those emissions were discussed in-depth at last week U.S. Mountain Community Summit, which Real Vail covered for the Vail Daily (see story re-posted below).

Colorado was already in the process of adopting California’s Low Emission Vehicle (LEV) standard – a separate protocol allowed under the EPA’s Clean Air Act because California already had more-stringent state laws limiting emissions.

RealVail.com covered both the LEV standard and the proposed ZEV standard for Colorado Politics in October and Real Vail in November. And here’s the press release from the Polis administration on last week’s executive order:

Gov. Polis signs executive order supporting Colorado’s transition to zero emission vehicles

DENVER — Gov. Jared Polis today signed an executive order outlining a suite of initiatives and strategies aimed at supporting a transition to zero emission vehicles

“Our goal is to reach 100 percent renewable electricity by 2040 and embrace the green energy transition already underway economy-wide,” said Governor Jared Polis. “Today’s Executive Order will strengthen our economy and protect the wallets of consumers across the state. As we continue to move towards a cleaner electric grid, the public health and environmental benefits of widespread transportation electrification will only increase.”

Colorado has taken significant steps toward the transition to electrified transportation, for passenger cars and heavy-duty vehicles such as buses. The state offers a $5,000 tax credit for passenger electric vehicles (EV)s; partners with the private sector to build fast charging stations along Colorado’s major highways; allocates a portion of Volkswagen settlement funds to support vehicle electrification; and has adopted a goal of 940,000 EVs on the road by 2030. The state is also a signatory to the Regional Electric Vehicles for the West (REV West) Memorandum of Understanding which creates a framework for collaboration in developing an Intermountain West Electric Corridor. The Colorado Air Quality Control Commission recently adopted Low Emission Vehicle (LEV) standards. Today’s announcement builds upon these past successes in order to achieve the goals set by the state, achieve our climate targets and reap the billions of dollars in economic benefits.

The executive order includes the following directives:

- Create an interdepartmental transportation electrification workgroup, to develop, coordinate and implement state programs and strategies to support widespread transportation electrification across the state.

- The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment shall develop a rule to establish a Colorado Zero Emission vehicle program, and shall propose that rule to the Air Quality Control Commission no later than May 2019.

- The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) shall revise the state Beneficiary Mitigation Plan, which describes how the state will allocate nearly $70 million received in trust funds due to the settlement of the federal Volkswagen emissions case. The revised plan will focus all remaining, eligible investments on supporting electrification of transportation, including transit buses, school buses, and trucks.

- The Colorado Department of Transportation

(CDOT) shall develop a department electric vehicle policy and plan designed to

assure that state transportation investments and programs support widespread

transportation electrification aligned with the articulated goals and

strategies outlined by the above mentioned workgroup.

Read the full executive order here.

Here’s the re-post of Real Vail’s coverage for the Vail Daily of building emissions discussed during last week’s U.S. Mountain Community Summit in Vail:

‘Not stack-a-shack’ anymore: can modular homes save ski towns and the world?

Can modular homes solve the affordable housing crisis in Vail and other ski towns across the West, and maybe even the save the planet as an added benefit? Maybe, but it’s still early days in the prefab revolution, cautioned developers and experts in the modular industry this week at the inaugural U.S. Mountain Community Summit in Vail.

“It’s an evolving industry that is getting better every day,” said Michael O’Connor, principal and chief operating officer of Triumph, the development company that used modular construction at the Town of Vail’s Chamonix local’s housing project in West Vail. “I’m a believer. But it’s got its own unique challenges.”

Triumph is also currently undertaking a 139-unit modular project in Truckee, Calif., with three different prefab companies providing the units that are predominantly built in a factory setting and then shipped to the development site. The idea is to control variables in on-site traditional construction such as mountain weather, pricey local labor and other factors.

“So many people are recognizing the difficulties that California is kind of leading the country in, like limited labor pool, very expensive local subcontractor base, projects too expensive, taking way too long to build,” O’Connor said. “You can control that risk by doing it in a controlled environment in a factory and get two thirds of the project built and limit your exposure.”

Steve Glenn, founder and CEO of Plant Prefab in Rialto, Calif., said modular construction can streamline the building process, cut down on waste and basically make buildings so much more efficient and environmentally sustainable.

Buildings as a category in the United States, Glenn said, consume more energy through lighting, heating and cooling (39 percent) than both industry (29 percent) and transportation (32 percent), adding that 40 percent of all raw materials that are extracted on the planet are used for building materials.

“So the bad news for those us who believe there is increasingly bad climate change is that the buildings that we live in and play in and learn in and work in are the worst of all,” said Glenn, whose company spun off of LivingHomes, which has had dozens of its homes LEED certified. “The good news is the technology to dramatically reduce the energy, water and resource use exists, and it’s increasingly no more expensive than non-sustainable materials.”

Plant Prefab uses certified materials that reduced outgassing, solar energy, far more efficient insulation and more of it than is mandated, LED lights, energy efficient appliances and water systems that recycle for irrigation. Their homes are modular but very contemporary, and actually cost-competitive in the Vail Valley, O’Connor said after Glenn’s presentation.

The problem is that California and other more populous West Coast states are sucking demand their way, and modular companies have recognized they can get $120 a foot out there and maybe only $100 a foot in Colorado, so they’re heading west, O’Connor said. There are some start-up companies coming into Colorado, including one in Grand Junction, but Chamonix units were trucked in from a company in Boise, Idaho, called Nashua, and transport adds costs.

While Chamonix made sense as a modular project, O’Connor said it’s not a slam dunk that future workforce or local’s housing projects in Vail will continue to be cheaper and more efficient with prefab. One of the hurdles is financing, with most banks refusing to close on construction loans until a building permit is pulled, but modular companies want their money up front.

“Financing it is completely out of synch with what’s typical, and that’s challenging,” O’Connor said. “The financing community has not completely figured it out, but they’re coming around.”

Glenn said US Bank has started working on modular-specific loan products that could reverse that trend, but he admits his company has yet to do an affordable housing project in a mountain community. Neither has Brian Abramson, co-founder and director of business operations for Seattle-based Method Homes, which has worked in ski towns on the market-force side.

Abramson strongly believes modular construction, especially technological advances like wet-core construction — with all the rooms with plumbing prebuilt — can help solve the acute housing crisis in both urban and mountain communities.

“The same problems that are happening in mountain towns are amplified in our market because of dramatic cost of living increases, real estate increases, so, especially in the affordable housing space, there’s a lot of skepticism [of modular in Seattle], more so than I heard here, which is actually really validating to hear how much it’s been embraced in the mountain communities,” Abramson said.

Microsoft on Wednesday announced it’s spending $500 million, mostly on loans, to help solve the housing crisis in the Seattle metro area, where it’s based, and Amazon has committed $2 billion to combat homelessness across the nation. Amazon is also an investor in Plant Prefab, Glenn said, adding he’d like to see policymakers begin regulating with modular in mind.

That could include onsite building inspections at the modular factories, or even zoning laws that are more amendable to multi-family modular projects.

“Minneapolis just got rid of single-family zoning. If you have a home in a single-family home zone area, you can now do multi-family anywhere in Minneapolis,” Glenn said. “Obviously, the number of units are limited by the size of your lot, but that’s spectacular. That’s going to have a dramatic effect on creating more housing more efficiently. I hope more cities do this.”

Glenn doesn’t see that necessarily happening in mountain towns, but it’s a solution for cities, and O’Connor said more and more modular companies such as Glenn’s and Abramson’s are building beautiful contemporary prefab homes that anyone would want to live in.

“It’s not like a trailer anymore,” O’Connor laughed. “It’s not stack-a-shack.”