Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

The great ski train debate: Will skiers, workers ever ride the rails in Colorado?

Passengers relax on Amtrak’s California Zephyr, which follows the Colorado River and passes through a remote corner of Eagle County (Chase Woodruff, Colorado Newsline photo).

In the summer of 1960, Rod Slifer quit his sales job at an office supply store in Denver and joined a friend riding three-speed klunker bikes to Union Station. There, according to the new book “Rod Slifer & the Spirit of Vail”, they jumped on a train to Glenwood Springs, got off and rode their bikes the rest of the way to Aspen, camping overnight near Carbondale. That’s because passenger rail service between Glenwood Springs and Aspen had shut down in 1949, and freight rail only lasted until 1969. Now those tracks are gone altogether in favor of a trail.

When Slifer, a newly minted Aspen ski instructor, followed ski school director Morrie Shepard to a brand-new ski area rising out of a sheep pasture that would become Vail in May of 1962, passenger rail service just off the backside of Vail Mountain to the old railroad town of Minturn was in its waning days, shutting down to the public just a couple of years later in 1964.

The death of U.S. Postal Service mail trains in the 1960s, coupled with the rise of the interstate highway system, car culture and the airline industry, all conspired to end robust passenger rail service that grew out of the mining booms of the late 19th century and saw railroad companies battling – sometimes quite literally with hired gunslingers – to build perilous rail routes through the Rockies in spectacular places like Gore Canyon, the Royal Gorge and the Moffat Tunnel.

So while Europe expanded its rail network with high-speed passenger trains and rail routes to famed alpine resorts such as St. Moritz, Zermatt and St. Anton, the United States passed on the concept of ski trains except for a handful of places such as Sun Valley and Winter Park. That trend could be reversing, however, as mountain highways in Colorado and other western states have become clogged with cars and semis, often shutting down for hours on end in winter weather and deeply impacting ski-town economies.

In the 60s it seemed ludicrous to imagine that Colorado’s system of state and interstate highways would become overwhelmed by 2023. Colorado Highway 82 into Aspen, for example, was a bucolic two-lane road in Slifer’s day, and the nearby train tracks seemed like a relic of Aspen’s glorious silver-mining boom nearly a hundred years earlier. But the modern boom of rampant real estate speculation, tourism and the ski industry has made Colorado’s most famous ski town a victim of its own success. And the derisive moniker “Killer 82” still applies to the highway.

That’s if you can even get as far as Glenwood Springs from Denver on four-lane Interstate 70 through the Eisenhower Tunnel at more than 11,000 feet in elevation, or Vail Pass at 10,600 feet. Glenwood Canyon – the engineering marvel that completed I-70 as the main east-west highway through Colorado in 1992 – is now frequently hit with lengthy closures due to the 2020 Grizzly Creek Fire that scoured the canyon of vegetation and made it increasingly susceptible to massive mudslides. Rail service through the canyon has seen fewer prolonged shutdowns in recent years.

I-70 through Glenwood Canyon can be a muddy, impassible mess (CDOT photo).

What’s reviving rail as a transportation alternative in the minds of many Coloradans, who as soon as 2024 could be asked to vote to fund passenger rail on the Front Range from Fort Collins to Pueblo, is the inability of the state highway department to keep up with an exploding population. According to the Colorado Department of Transportation, CDOT has only been able to increase lane miles (basically road capacity) 2.6% between 1990 to 2023. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Colorado’s population during that time has increased from 3,304,000 to an estimated 2023 population of 5,913,000, or 78.8%. If the roads seem crowded, that’s why.

The trains to Aspen, however, will likely never be back. Local entities purchased the Denver & Rio Grande railroad right-of-way in 1997, and while commuter rail was explored, those plans were rejected in favor of a rails-to-trails project that in the 2000s led to the 42-mile Rio Grande recreational trail between Aspen and Glenwood Springs. Train buffs were not happy.

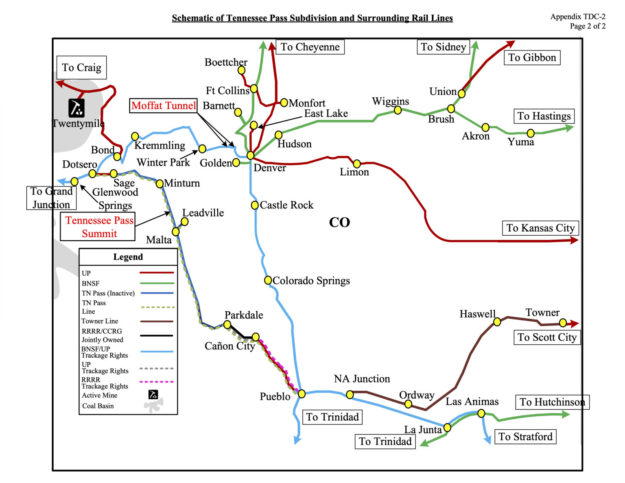

That’s nearly what happened here in Eagle County, where Union Pacific’s dormant Tennessee Pass rail line travels along the Eagle River from Dotsero in the west through Gypsum, Eagle, Edwards, Avon (where a gondola and a transit center connect to Beaver Creek), Minturn, Red Cliff and on over Tennessee Pass to Leadville. When the Southern Pacific and Union Pacific railroads merged in 1996, UP tried to formally abandon the line but federal rail officials rejected the plan. Still, the line was shut down (the last freight trains rumbled southeast to Pueblo in 1997), and local recreational trail enthusiasts came up with a plan to make the rails-to-trails switch.

“The big stumbling block was UP,” says former longtime Vail Town Council member Kevin Foley, who served on the rails-to-trails committee back then. “UP wouldn’t give us the time of day after we got everything pretty much said and done. The state gave us a little six-by-six highway sign, and it says, ‘Governor’s Smart Growth and Development Award 1997’. So that’s 26 years ago, and nothing’s happened.”

Actually, quite a bit has happened along the dormant Tennessee Pass Line: Homes, schools, stores and more have been built alongside the tracks, vandals tore up signals, realtors and residents alike pretty much forgot that trains used to rattle along those tracks between Dotsero and Pueblo – and possibly could again. Foley says he’d still like to see the rails-to-trails plan enacted but is open to passenger rail to get workers to their jobs and skiers to the slopes.

“Yeah, I would prefer [trails only]. But the right of way is so big that you could still put a crushed gravel path alongside the rail and accommodate both [a train and a trail],” Foley says. “If you can do rail, it’s feasible, people are going to use it and you can get cars off the interstate, then sure, why not? We’ve got to do the right thing for the climate and for the earth.”

That’s exactly what billionaire landowner Stefan Soloviev had in mind when he first broached buying the Tennessee Pass Line from UP for $10 million back in 2019. Soloviev in 2020 offered one passenger train a day between Pueblo and Minturn to sweeten the deal and garner local support, as well as recreational trails along the right of way. The New York developer, however, made it clear he was primarily interested in transporting corn from his vast agricultural holdings in Kansas, Colorado and New Mexico more directly to West Coast docks. Earlier this year, after buying a second Colorado railroad, Soloviev said he was no longer interested in Tennessee Pass.

Rail advocates estimate that moving freight and people by train instead of diesel semi-trailer trucks emits anywhere from 50% to 75% less carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Eagle County Commissioner Kathy Chandler-Henry is interested in the climate benefits, but she also thinks the I-70 bottleneck needs to be solved, and that rail should be part of the solution. And in 2022, voters passed a new transit tax to form the first-ever region-wide Eagle Valley Regional Transit Authority (RTA).

“It’s pretty dire — that big artery coming right through the mountains, and it’s not going to get any better,” Chandler-Henry said of I-70 closures. “We can’t pave our way out of this, so we’ve got to have an alternative. This Moffat Tunnel lease, that does seem like our opportunity to make the railroad talk to us. What is it, God and then the railroads as far as who runs things?”

The state of Colorado owns the 6.2-mile Moffat Tunnel where UP’s active Central Corridor Line passes under James Peak in the Continental Divide at Winter Park. Trains coming up from Denver, including the Winter Park Express ski train in the winter months and Amtrak’s year-round California Zephyr (from Chicago to the Bay Area) pass through the tunnel and then follow the Fraser and Colorado rivers to Dotsero, where they head west through Glenwood Canyon.

UP’s 99-year lease for $12,000 a year to use, operate, maintain and insure the Moffat Tunnel expires Jan. 6, 2025, and the Colorado Department of Transportation has taken the lead in renegotiating the deal, which opponents of a proposed new oil train in Utah hoped the state would use as leverage to derail that project. The Uinta Basin Railway, which would send up to 350,000 barrels of oil a day along the endangered Colorado River, was substantially delayed by a costly Eagle County lawsuit forcing the project back for more extensive environmental review.

Eagle County is unique in that it has the two major rail lines through the Colorado Rockies meeting at a community, Dotsero, where the Eagle and the Colorado rivers also come together. According to the book “A Compendium of Curious Colorado Place Names”: “Although it’s been suggested by some that this name … comes from a word in the Ute language meaning ‘something unique,’ the better theory is that the name came from a start-of-the-line marking on an old Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad map –’.0’ — that is, “dot-zero.”

Could “Dot-zero” now be the place where a Colorado passenger railroad revival is launched? Not according to the state, which – in the mountains at least — is starting off by exploring the possibility of commuter and tourist service between Craig and Steamboat Springs. A UP spur heads northwest off the Central Corridor Line from Bond in Eagle County along the Yampa River through Steamboat Springs and all the way to Craig. It connects to the Yampa Valley Regional Airport near Hayden, which is essentially Steamboat’s international airport. That would put two Alterra-run ski areas, including Winter Park, on the same rail line.

An Alterra spokeswoman says the Denver-based ski company (and chief rival of Vail Resorts) is interested in “exploring a broader transportation system solution for our region … with expanded affordable housing options” and new transportation experiences for guests.

Local leaders like Routt County Commissioner Sonja Macys say “the conversation around passenger rail in Northwest Colorado is changing dramatically. It’s one of these things that I’ve been looking at for a long time because I’ve been working on coal transition stuff since 2008. We’re sort of getting to a place where all of the arrows are pointing in the direction of actual, I don’t want to say imminent success, but not as long-term as one would’ve thought.”

That’s because Xcel Energy’s coal-fired Hayden Generating Station, which receives coal by rail, will no longer burn the fossil fuel starting in 2028. State Rep. Meghan Lukens, a teacher in Steamboat Springs, says the state is looking to transition the still-very-viable rail lines to transport workers from Craig and Hayden to Steamboat Springs, as well as tourists to Steamboat.

State Sen. Dylan Roberts, who grew up in Steamboat and until recently lived near the dormant railroad tracks of the Tennessee Pass Line in Avon, had this to say: “Our understanding of where CDOT sees opportunity for using federal infrastructure dollars most effectively at the moment is connecting Winter Park to Steamboat/Hayden/Craig via State Bridge/Bond and then go north through Yampa and Oak Creek. I, of course, would support passenger rail through Eagle County to Leadville as well but it would likely be a completely separate project, is my understanding.”

CDOT spokesman Bob Wilson wrote that: “We remain interested in the Tennessee Pass Line, and have identified it as a recommended corridor for consideration of future passenger rail service, although this identification will be in the 2023 Rail Plan update (and a vision white paper) that haven’t been published yet … The lease of the Moffat Tunnel likely has no impact on the potential for the UP or other partners to re-open the Tennessee Pass subdivision, but may be a component of the negotiations as we look forward.”

Roberts led the state-level charge to block Utah’s oil trains, and he and Lukens are planning to spearhead the Moffat Tunnel lease negotiations and possible commuter and tourist train projects in the State Legislature during the 2024 session starting in January.

Christof Stork, chief scientist for a seismology company in Golden and a tech entrepreneur who has been studying, writing about and advocating for an Eagle County passenger rail line since 2016, doesn’t understand the state push for Steamboat ahead of Eagle County, where he says a dedicated passenger service without freight conflicts would be ideal.

“The Winter Park Express ski train is an example of what you don’t really want,” Stork says. “The problem is that it is painfully slow and it runs only once a day. It takes 2.5 hours to go 50 track miles. It is mainly for fun, not as an effective method of transportation. Denver to Steamboat on a train will take 5-6 hours, so no thanks. It goes so slow because it shares the track with freight; hence, it has to go at freight speeds, it is a heavy train, and it can’t be broken into four trains leaving at different times.”

Because there’s currently no freight service on the Tennessee Pass Line, Stork argues that faster commuter trains could be used, with rail lines running right through the downtown areas of Gypsum and Eagle (near the Eagle County Regional Airport), Wolcott, Edwards, Avon, Minturn and Red Cliff. He puts the cost of refurbishing the line at between $50 million and $100 million.

“In my analysis, the economics of this line would be strong because (1) the right-of-way already exists, which is often 95% of the cost, (2) potential high revenue tourist traffic in the winter and summer, (3) employer support to access to west-side housing, (4) federal funding, and (5) significantly increased property values along the line,” Stork writes.

Former Vail Mayor Kim Langmaid, founder of the Walking Mountains Science Center in Avon, advocates for new electric trains on the tracks between the Eagle County Airport and Vail (a few new miles would have to be added east from Dowd Junction to the Vail Transportation Center in the I-70 median). Langmaid recently told RealVail.com: “I’ve always thought that bringing back the trains specifically for commuters and to support tourism would be a great move for us. All of the communities involved in the Climate Action Collaborative want to reduce the number of vehicles on the road. The train could be a great solution.”

But newly minted Vail Mayor Travis Coggin is skeptical.

“Who does it serve?” Coggin said. “There’s a lot of economic challenges with it, and we already have amazing train tracks: They’re called I-70, and it goes right there. So I feel like really looking at having the RTA fit that mold and have that great bus service that connects to the airport. I would love to beef up bus service. It’s flexible. Yeah, our valley might be linear, but people live up [off the valley floor] so they’ve got to get down to [public transportation]. Yeah, the rail line’s there, but it gets you to Dowd Junction and then what are you doing for the last three miles?”

Harry Frampton, a partner of Rod Slifer’s in Slifer Smith & Frampton Real Estate, isn’t convinced. Frampton is the founder and chairman of East West Partners, one of the companies that redeveloped Denver’s Union Station and built Riverfront Park in an abandoned railyard in Denver. His company also developed hotels and real estate in Beaver Creek and Avon, including the gondola-connected Westin Riverfront along the Tennessee Pass Line tracks there.

“It’s been forever since those trains came through there, and I think it would be bad for our community for that to happen,” said Frampton, a Vail resident. “I know nothing about the economics of railroads, but the magnitude of money of rebuilding that rail line and then making it work, I would be willing to bet anything it never happens.”

In November, Avon Mayor Amy Phillips told RealVail.com that trains aren’t very high on her priority list after traffic, parking, housing, daycare and other top concerns, but if it is revived, she said it needs to go to Vail.

“Avon has not taken a stance,” Phillips said of the idea of commuter and tourist trains on the dormant Tennessee Pass Line. “I personally think the only way it will be palatable to the community is if there is a plan that includes passenger service all the way to Vail … from (the Eagle County Regional Airport) for travelers and residents. Avon Station is already in place for such service. Other stops would need to include park-and-ride services and could easily extend to Glenwood Springs.”

Editor’s note: A version of this story first ran in Vail Valley Magazine and the Vail Daily.