Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Conductor who revived ski train wants to fix I-70 for snow riders with truck-by-train rail bridge

Brad Swartzwelter during his working days as conductor of the Winter Park Express Ski Train (courtesy photo).

The longtime Amtrak train conductor credited with crafting a business plan that helped revive the mothballed Winter Park Express ski train in 2017 now has a plan to get at least 60% of the commercial truck traffic off of Interstate 70 and free it up for skiers and snowboarders.

Brad Swartzwelter, 60, retired as conductor of the ski train last spring after 30 years with Amtrak, the federal rail agency that runs the popular, seasonal and recently expanded ski train service between Denver’s Union Station and the city of Denver’s Winter Park Resort.

“I-70 congestion has cost us dearly in the snow sports industry, and it is my absolute mission in life … to get people safely, conveniently and economically up to our economic engine, which is skiing and snowboarding,” Swartzwelter said in a recent phone interview.

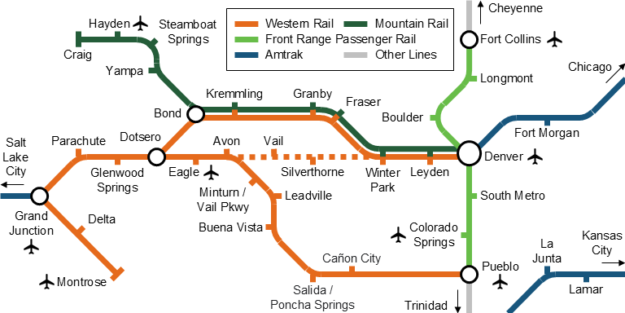

Swartzwelter’s idea, based on successful European models, is a truck-by-train “rail bridge” over the Colorado Rockies using Union Pacific’s existing Moffat Tunnel Subdivision rail line that runs from Kansas in the east through Denver to Grand Junction and on to Utah in the west. Entire semi-tractor trucks would be driven onto flatbed rail cars and drivers would then have the option of sleeper cars for the nine-hour trip across the state in either direction.

“I-70 is our biggest problem in this state. The congestion is unbearable,” Swartzwelter said. “All we need is one trucker making a mistake to cause one of the 99 shutdowns that pummels us and takes away millions of dollars, especially from places like Vail. Removing the trucks from I-70 and putting them in a different corridor would relieve well over 70% of the problem.”

In a recent letter to Gov. Jared Polis, Vail Mayor Travis Coggin pointed to the state’s own analysis that estimates nearly $2 million in economic losses for every hour I-70 is fully shut down by a crash. That happened 99 times in 2024 for a total of 161 hours and more than $320 million in statewide economic impact just last year. So far 2025 is on track for similar numbers.

Coggin has called for dramatically higher fines for truckers who violate the state’s chain laws, the town is drafting an emergency ordinance increasing penalties, and Coggin made the rounds on Denver TV stations over the particularly snarled Presidents Day weekend, when I-70 shut down numerous times at Vail Pass and elsewhere during an intense snow cycle.

Asked in an email late last month about Swartzwelter’s truck-by-train idea, Coggin wrote: “If it’s a viable solution that safely and quickly gets semis off I-70, then I would be all for it. Since I did those TV interviews, I’ve had several miserable Vail Pass experiences.”

A recent semi-truck crash in Glenwood Canyon (CDOT photo).

Getting trucks off I-70

Swartzwelter estimates Union Pacific’s rails between Grand Junction and Denver are at about 30% capacity since coal’s heyday in the 1980s when about 30 trains a day went back and forth through the Moffat Tunnel. These days there are about six oil trains a day and a few passenger trains in the form of Amtrak’s long-distance California Zephyr, the seasonal ski train, and the high-end, seasonal, Canadian-owned Rocky Mountaineer from Denver to Moab, Utah.

Colorado, which owns the Moffat Tunnel, recently reached the framework of a new lease deal that allows the state up to three free roundtrip passenger trains on Union Pacific’s tracks in exchange for the company using the 6.2-mile tunnel. That doesn’t include the Winter Park Express, which the state hopes to expand on to Steamboat Springs and Craig (Mountain Rail), and the California Zephyr, which connects Chicago and California’s Bay Area on a daily basis.

Swartzwelter proposes floating a voter-approved billion-dollar bond issue that would provide the funding to build the truck-by-train rail bridge, including specialized terminals for loading trucks west of Grand Junction and east of Denver, as well as passenger rail projects such as Mountain Rail’s Oak Creek to Steamboat section and possibly a revival of the Tennessee Pass Line.

Truck drivers from the West Coast would be able to get to western Colorado in one shift, load their semi, get nine hours of federally mandated sleep in a sleeper car, unload in eastern Colorado and continue on east, or vice versa.

“That driver would essentially be able to continue operating nonstop, also while sleeping,” Swartzwelter said. “The beauty of it is, with a train departure every three hours going both directions from both terminals, with 70 trucks per train, we could get 1,120 semis a day off of I-70.” He estimates there are currently about 2,000 semis a day on the Colorado stretch of I-70.

“The model for this whole thing is Austria. They were sick of their highways being congested and destroyed by the trucks going from Germany to Italy,” said Swartzwelter, a skier whose wife is from Vienna. “They’ve got nothing on us except for political will.”

A company called ROLA Rolling Road started a service on the Austrian Federal Railway, loading trucks onto flatbed trains and running them across the Austrian Alps. It’s also done through the Channel Tunnel, or “Chunnel,” between London and Paris.

“How do we remove commercial vehicles from the I-70 corridor? When there’s accidents that happen at a higher rate with commercial vehicles, and they’re more catastrophic, and they shut down I-70 for longer, that impacts everybody more dramatically,” said Glenwood City Council member and former mayor Jonathan Godes. “This [rail bridge] is a really innovative solution.”

Godes credits the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) and the state legislature with spending to improve I-70, funding buses and passing laws to compel truckers to chain up and stay in the right lane in critical stretches such as Glenwood Canyon and Dowd Junction.

But problems persist on I-70 as the state’s population grows and it’s more and more difficult to house law enforcement and highway workers in the high-priced real estate of mountain towns. Encouraging alternative forms of transportation only goes so far, he says, because “everybody loves public transportation for other people” and buses are often stuck in the same traffic.

He also isn’t worried about increasing freight rail through Glenwood with the rail bridge, as long as it isn’t oil: “[Trucks are] coming through Glenwood regardless. They’re either coming through on I-70 or they’re coming through by rail. [The rail bridge] is a great conversation to have.”

An oil truck speeds by the new Grand Hyatt Deer Valley at Deer Valley East along Highway 40 in Utah with the Jordanelle Reservoir in the background. It’s on its way back to the Uinta Basin after depositing its load near Union Pacific’s rail line to Colorado (David O. Williams photo).

Do oil and skiing mix?

Swartzwelter has one major concern about his concept, though, and it has to do with the surge in oil production in northeastern Utah that spurred the proposed 88-mile Uinta Basin Railway plan, which Eagle County and a coalition of environmental groups sued to successfully delay, pending a U.S. Supreme Court ruling on the case.

“The one thing that might kill [the rail bridge idea] is that the crude oil trains from Vernal, Utah, that are being first trucked … down to Wellington [Utah] to be loaded onto oil cars that are then run on trains [through Colorado],” Swartzwelter said.

“America needs that energy. We don’t want to try and stop those oil trains, but those oil trains will definitely slow down and cause great trouble to whatever we try and do on that line, whether it’s passenger rail or a truck by train rail bridge, or even running the ski train,” Swartzwelter added. “I was late 30% of the time because of the very few oil trains that are running today. The Uinta Basin Railway, to me, is a nail in the coffin of the Colorado River.”

Utah’s waxy crude oil is too thick to be sent through pipelines, which is by far the cheapest way to move oil, so it needs to stay heated and get all the way to refineries on the Gulf Coast to then be processed into gasoline or plastics and shipped to global markets.

But instead of using train tracks along the scenic headwaters of the endangered Colorado River, or building the estimated $2 billion, 88-mile Uinta Basin Railway to Union Pacific’s Moffat line, Swartzwelter recommends the oil be trucked straight north to Wyoming with around $100 million in highway improvements on remote U.S. Highway 191.

It’s about 110 miles on 191 from Vernal, Utah, to Rock Springs, where Union Pacific owns the underutilized, double-track Overland Route that runs east-to-west across Wyoming before connecting with north-south rail lines on Colorado’s Front Range.

“It is almost the same number of miles to run those heated tanker trucks north to Rock Springs instead of south to Wellington [Utah],” Swartzwelter said. “At Rock Springs, [Union Pacific’s] got a double track mainline that would be far more efficient rail-wise to load those oil trains there and then run them across the grasslands of Wyoming and then south to the Gulf Coast, rather than through the extremely fragile canyons and curves and steep, high-altitude grades of Colorado, where one accident has the potential of putting a million gallons of raw, waxy crude into a river that 40 million people depend upon.”

Editor’s note: A version of this story first ran in the Colorado Springs and Denver Gazette newspapers.

The Winter Park Express Ski Train in Fraser with Winter Park Resort along Highway 40 in Colorado in the background. About six oil trains from Utah per day currently use the same train tracks through the state-owned Moffat Tunnel, below (David O. Williams photos).

David O. Williams

Latest posts by David O. Williams (see all)

- Neguse, Bennet call for halt to BLM emergency rule aimed at increasing Utah oil-train traffic - June 23, 2025

- The O. Zone: Trump’s long list of broken campaign promises just jumped to yet another forever war - June 23, 2025

- The O. Zone: Coming to Vail this summer? Leave fireworks, risky fire behavior at home - June 20, 2025

Mark Bergman

March 17, 2025 at 1:51 pm

How does the additional cost of using the the train compare to the cost of driving the truck?

David O. Williams

March 17, 2025 at 2:27 pm

Good question, Mark, and, of course, the cost of maintaining and expanding the roads to meet our growing population needs. I think I hear you saying it should at least be studied.

Brad Swartzwelter

March 17, 2025 at 6:54 pm

When factoring in all inputs to truck operation (fuel, tires, engine and transmission wear, insurance, USDOT mandated rest, etc.) between Grand Junction and east of Denver, I believe costs will be in favor of the train at $700 per trip for a truck and one driver. If tolls or delays are added, the train is the clear winner. In addition, truck companies have the added chance to run a single driver from the Los Angeles basin to Grand Junction on a single shift. The driver can then sleep 8 hours on the train in a private room. At that point the driver can continue on to Kansas City or Dallas – one driver non stop from west coast to the Missouri River Valley or beyond! That is a game changer in motor carrier economics.

Mark Bergman

March 17, 2025 at 3:10 pm

Yes! I was most curious if the guy proposing the truck train and suggesting $1B in funding has studied the operating costs. On the face of it, it sounds like a decent way to reduce traffic. I’d like to know if it’s practical or a pipe dream.

David O. Williams

March 17, 2025 at 3:59 pm

It needs a proper state study factoring in hard numbers on truck traffic (how much interstate, how much local) and road repairs etc. Then it comes down to how interested Union Pacific is in boosting use of the Moffat Subdivision. The only reason Mountain Rail is moving forward is UP was losing coal train traffic due to the shuttering of Craig and Hayden power plants and approached the state about passenger rail. With Moffat line now down to about quarter capacity, one would think they’d be interested in something like this. I’ll be reaching out to them and other stakeholders in follow-up stories, so stay dialed into Real Vail. Thanks for reading.