Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Union organizer calls paying patrollers in powder ‘economically ignorant’ in Colorado

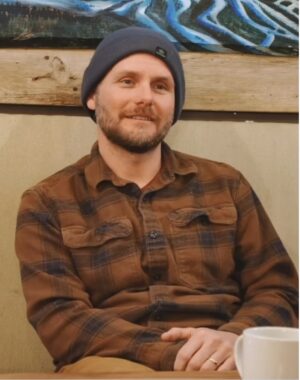

When Breckenridge Ski Patroller Ryan Dineen first moved to the most popular ski town in Colorado in 2007, he paid $400 a month for a room in a house and figured out how to make enough money to live in a place tourists pay tens of thousands of dollars to visit every ski season.

The very next season Breckenridge owner Vail Resorts, headquartered in the suburban Denver city of Broomfield, introduced the revolutionary Epic Pass for $579 for adults that included unlimited snow riding at Breckenridge, nearby Keystone, Vail, Beaver Creek and Heavenly on the California-Nevada border near Lake Tahoe.

Seventeen years later, while the adult Epic Pass price increased nearly 70% to $982 this season, it now includes 42 unlimited core resorts in four countries – a 740% increase in available ski areas on one pass. And it has a competing pass in the form of Denver-based Alterra Mountain Company’s Ikon Pass that provides unlimited access to 14 core resorts for $1,249 (early season).

In the ever-escalating arms race between the two largest companies most bent on outright acquiring ski areas as well as adding partner resorts (both are affiliated with nearly 40 more ski areas apiece), Dineen said there has been some serious collateral damage since skiing’s heyday.

“We’re seeing the confluence of several things,” said Dineen, who is the president of the Breckenridge Ski Patrol Union. “One is the consolidation of the ski industry and the increased corporatization of the ski industry — looking at it as if [ski areas] are an acquisition to be stripped down to its bones and made to perform at its most profitable level possible.”

Even as the state’s population has more than doubled since 1980 – the last time a major ski area (Beaver Creek) was built from the ground up – it’s become clear no more resorts are coming online, putting a premium on terrain expansion and lift-capacity increases.

“So we’re adding to the complexity of these mountains, we’re adding to the overall structure of these mountains, we’re adding to the capacity of these mountains,” Dineen said. “Obviously, Breckenridge can hold far more people now than it could even the early 90s, and there’s that many more people coming here on any given day.”

The increased crowding has led to a higher level of intensity for ski patrollers and other resort workers charged with keeping lifts operating and snow conditions safe for more and more snow riders, Dineen said. On top of job-related stressors, Dineen said all of the apartments he rented when he first came to town are now short-term rentals, and many more people have relocated to Breck to work remotely – making it difficult for resort workers to live what’s left of the dream.

The post-COVID influx of wealthy remote workers, swelling demand for outdoor recreation, and lack of affordable housing in ski towns has also led to a collective realization of the power of labor, Dineen said, pointing to the ski patrol strike at Vail’s Park City Mountain Resort over the holiday that led to significant wage gains and a class-action lawsuit filed by an angry vacationer.

With its stock price down 50% since 2021, a Vail Resorts’ shareholder demanding heads roll at the executive level, Crested Butte lift maintenance workers contemplating their own strike, and Keystone ski patrollers now renegotiating their contract with Vail Resorts, Dineen said there is bound to be some spillover from the Park City strike into Colorado’s ski labor market.

“I definitely see [the Park City contract] as setting a precedent,” Dineen said. “The movement that our union contracts have made over the last … six years has affected wages across the entire ski industry,” Dineen said. “I do expect [Park City] to impact both the wages that Keystone is proposing and probably the wages that Keystone’s willing to accept.”

Dineen, an organizer for the United Mountain Workers, with 16 individual unions, said there’s one more huge change he’s seen in the ski industry since the mid-aughts and dating back to the pre-consolidation days in 1990s: The “mythology of the ski bum” is all but dead.

“That’s a story we all kind of love to tell ourselves, and it’s kind of this spirit of skiing that we wanted to keep alive as long as possible, but let’s make no mistakes, skiing brings hundreds of millions of dollars to the state of Colorado,” Dineen said. “This industry makes money for not just the investors, not just the towns around us, but the entire state and region, and to ignore that and pretend that we should be paid in powder is economically ignorant.”

Vail Resorts did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Editor’s note: A version of this story first ran in the Colorado Springs Gazette.

Thomas

February 9, 2025 at 5:31 pm

Ski instructors have it even worse off, most get paid by lesson hrs. I don’t know of anyone instructing 40hrs per week. Many are hard pressed for 30 hrs. That is all depending on lessons that sign up. I work at a place where full time instructors on the bottom of senority literally do make enough for Rent and food. I have never here of a snow sports school loose money. What they charge vs what the instructors are paid is pure Slavery.