Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Vail digs deep, diversifies in search of clean-energy solutions to combat climate change

Holy Cross Energy CEO Bryan Hannegan, left, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, center, and Vail Mayor Travis Coggin at a geothermal event in Vail last summer (David O. Williams photo).

Editor’s note: Since this article first appeared in the winter edition of Vail Valley Magazine and was later reposted on the Vail Daily website, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has downgraded the smog status in Utah Uinta Basin, deadly wildfires are ravaging Los Angeles, the incoming Trump administration is targeting California’s emission standards that states such as Colorado have joined in a bid to stave off the worst effects of global climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels, and Holy Cross Energy announced its electric rates are now 40% below national averages.

What do you do when your upwind neighbor drives a coal-rolling monster truck, burns trash in his backyard and couldn’t care less about air quality, but also loves to ski, raft, rock climb and mountain bike and therefore sort of paradoxically seems to value the outdoors?

Do you get sideways with him by lecturing and demanding he changes his climate-wasting ways? Or do you hope time, maturity and, eventually, simple economics will get him to clean up his act and care a little more about preserving public lands and protecting his outdoor economy?

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, a Vail homeowner, seems to be taking the lead-by-example tack, refusing to call out the policy pitfalls of Gov. Spencer Cox and an almost unanimously Republican group of policymakers in Utah who are aggressively promoting the extraction and burning of fossil fuels despite the obvious, ongoing impacts of manmade climate change.

The closest Polis would come to doing a little bit of scolding was at the National Governors Association (NGA) meeting this past July in a sizzling Salt Lake City, where he called out ozone emissions coming into Colorado from “several states depending on the wind” as an argument for why his state should get a hall pass from the EPA for non-attainment of minimum ozone levels.

Polis, who accepted the NGA chair baton from Cox in July, declined to take a jab at one of the biggest sources of ozone pollution right on the Colorado border in northeast Utah – the massive oil drilling operations in the Uinta Basin area between Duchesne, Utah, and Dinosaur, Colorado.

Even a couple of weeks later in Vail, at an event promoting a groundbreaking geothermal project, Polis carefully stated his administration is “aggressively monitoring” Eagle County’s successful lawsuit that derailed the Uinta Basin Railway project aimed at dramatically increasing oil train traffic through Colorado – a ruling likely to be overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court. He did admit the majority conservative court reversing Eagle County’s legal victory “would have a major impact on our state for sure, in terms of transportation.”

Perhaps one of the reasons Polis seems hesitant to call out Utah on fossil fuels is because Colorado in 2023 was the fourth-largest oil-producing state in the nation, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, accounting for 4% of the country’s all-time record year for oil production. But at the same time, Colorado’s electricity generation has shifted from 68% coal in 2010 to 32% in 2023, and electricity from renewable sources (mostly wind) jumped to 39%.

Colorado’s turn toward carbon-free electricity blows past the national average of 21% renewable power in 2023 and Utah’s below-average 19% renewable share in 2023. And while Utah – the nation’s ninth-largest oil-producing state – has a voluntary goal of generating 20% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2025, Polis ran on a platform and has developed an ambitious roadmap for achieving 100% renewable power by 2040.

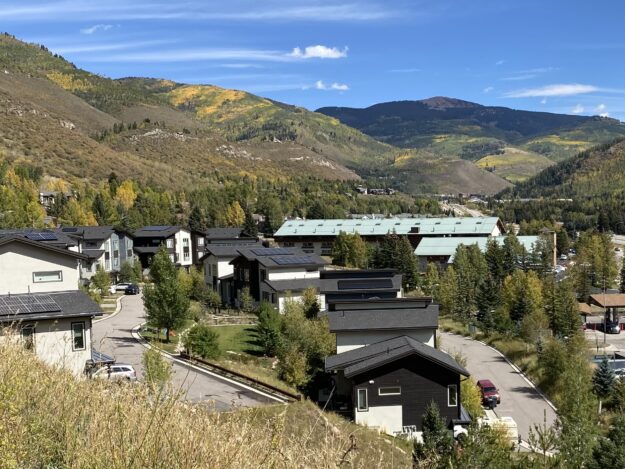

Solar panets atop Vail’s Chamonix townhomes in West Vail (David O. Williams photo).

Holy Cross Energy leading the way

But even the state’s lofty goal has Colorado as a whole lagging behind one of the most progressive power companies in the nation – the rural electric association known as Holy Cross Energy in Glenwood Springs, which has the notable distinction of serving two of the most globally recognized names in the ski industry: Vail and Aspen.

Named for the only fourteener in Eagle County – 14,009-foot Mount of the Holy Cross that dominates views from Vail’s Back Bowls – Holy Cross Energy in August achieved 80% renewable power for its members stretching from Vail in the east to Parachute in the west to Aspen-Snowmass in the south. The co-op is on track for 90% renewable electricity by the end of 2025 and 100% carbon-free power by 2030, which is 10 years ahead of the state.

At a September climate change panel discussion in Vail cohosted by Vail Mountain, Beaver Creek Resort and Walking Mountains Science Center, Vail Resorts Director of Sustainability Fritz Bratschie singled out the not-for-profit, member-owned Holy Cross Energy for praise:

“We’re very lucky to have an awesome, super-aggressive, one of the leaders in the renewable utility space that we don’t have to focus on as much here, but in the state of Utah, where we operate Park City [Mountain], the state and some of the utilities are not as progressive, not as forward-thinking on renewables and things like that,” Bratschie said when asked about a particularly challenging community partnership he’s had to deal with.

Bratschie described a concerted push by Vail Resorts, Salt Lake City, the town of Park City, surrounding Summit County, ski rival Alterra’s Deer Valley and Utah Valley University to force the hand of state and power utility officials to “allow customers that wanted to drive change to develop renewables. Five plus years in the making since we actually signed the deal, Elektron Solar came online in Utah in April. They’re going to provide 100% clean, renewable electricity for Park City Mountain and different percentages for some of the other stakeholders.”

One of the most common arguments against rapidly shifting electric grids entirely to renewable sources is that wind and solar are intermittent, battery and other forms or storage aren’t yet reliable, and that prices will inevitably go up. Holy Cross Energy President and CEO Bryan Hannegan pushes back on all of that.

“The real problem was how do we transition to clean energy, but in a way that doesn’t cost more, in a way that doesn’t jeopardize the reliability of service, in a way that’s safe and secure?” Hannegan said. “That’s the secret sauce that we’ve found. And what we’ve done is transferable to any community. It’s not because we’re paying more because we’re a rich community and can afford it. We’re actually saving money as we do it. If you look at our electric rates, they’re a good 10% to 20% lower than most of the other utilities in the state at this point.”

As an international outdoor recreation company with 42 ski resorts in four countries, Vail Resorts is clearly excited to have the company’s flagship and namesake ski area powered by such a trend-setting electric utility, but could they use their global branding reach to spread the Holy Cross model to less-progressive markets in red states like Utah? In some ways (Elektron Solar), they’re already doing so, but for a publicly traded company with lots of customers from Texas (No. 1 in oil, gas and wind power production), corporate advocacy can be a bit fraught.

Vail Resorts Director of Sustainability Fritz Bratschie, second from left.

“At Vail Resorts, we actively advocate and collaborate with stakeholders to promote policies and initiatives that support the transition to clean energy sources,” Bratschie responded. “Holy Cross Energy is one of our close partners who heavily impacts that transition, and Vail Mountain and Beaver Creek Resort are lucky to operate within Holy Cross’ territory. Not only do our resorts benefit from their work to increase renewable energy sources, but also the entire community. We work closely with Holy Cross to identify opportunities in which our operations can support the transition to renewable energy, both through investment in energy efficiency and mindful operations during critical peak times where renewable generation is not at its peak.”

The Climate Action Collaborative for Eagle County Communities found that in 2022 greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) in Eagle County rose 6% above the 2014 baseline. Collectively – including the Town of Vail — the group has set a goal of reducing GHG emissions 50% below baseline by 2030 and 80% by 2050, and the efforts of Holy Cross have reduced emissions from electricity by 38% since 2014. So why are GHG emissions overall still going up?

“That’s the other two thirds of the climate problem that we don’t talk about,” Hannegan said. “Everybody focuses on power, power, power. The truth is, in Colorado, we’re almost done with that when you look at the plans that all the utilities have filed. So now we’ve got to get onto buildings, now we got to get onto transportation, now we’ve got to get onto industry and figure out how to use that clean electricity as a fuel for those sectors.”

Holy Cross is providing free Level 2 electric vehicle chargers for any member who wants one, and Hannegan points out that at current rates Holy Cross members can cleanly power their EV for the equivalent of about $1.50 a gallon compared to an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle. Holy Cross, through its Power+ program, also fully finances batteries for homes and businesses and is considering doing the same for heat pump heating and cooling systems.

Meanwhile, Eagle County and several towns have been updating building codes to move toward electrification, something Hannegan hopes could be significantly boosted by geothermal drilling and the thermal loop system being developed in Vail to melt snow and ice on the streets. Not only will the project use natural heat from the earth’s crust to replace the current natural-gas-powered snowmelt system (one of the town’s largest sources of GHG emissions), but it will also be a place to store excess, or waste, heat generated from making ice at Dobson Ice Arena as well as chillers at hotels and other buildings throughout Vail.

Polis promoted state funding for the geothermal project, being implemented as part of Vail’s civic-area revitalization of the ice arena and library, as a high-visibility model for other communities to follow. The system will also allow Eagle River Water and Sanitation to offload its excess heat from water treatment into the loop in order to return cooler water to Gore Creek.

Hannegan says the system, and hopefully others like it, will be a place to park excess wind and solar power during peak times that otherwise has to be sold back at market prices, sometimes at a loss: “I would much rather take the excess renewable energy that I have on the system, serve all the electric load I can, but then with the extra, actually heat the water up in these thermal loops a little bit more and store that energy for a later use so that when we go to heat the buildings, instead of the water being in the loop at 55 degrees, maybe it’s at 56, and so we need less electricity to boost that 56 up to 68 or 70 or whatever the people want inside their building.”

Vail Resorts is all in on the concept as well.

“We are working closely with the Town of Vail and Holy Cross to explore the feasibility of using geothermal energy throughout the Town of Vail,” Bratschie said. “Vail Resorts is specifically exploring the opportunity to tie in and include some facilities in the geothermal system, aiding in greenhouse gas emission reduction for Vail Mountain and the Town of Vail.”

Vail Resorts on Oct. 1 announced a partnership with the Town of Vail and East West Partners to settle legal wrangling between the town and the ski company over the ill-fated Booth Heights workforce housing project in East Vail and team up on a fourth Vail Mountain base area development at the location of what was approved as Ever Vail in the mid-2000s but derisively became known as “Never Vail” after the 2008 housing collapse.

Connecting new and existing structures in Vail to a geothermal loop system is where the building sector, responsible for about a third of GHG emissions, can then start to see a major transition parallel to the power sector, Hannegan says. “Absolutely. And that becomes a really viable way to start decarbonizing buildings away from natural gas. Then once we’ve got a few of these projects under our belt and they’re working for a little while, then we can have a meaningful conversation about, well, should this be in the energy code?”

Geothermal is an arena where Utah, along with six other western states, has a solid head start on Colorado in terms of geothermal electricity generation, which accounts for about 1.5% of Utah’s overall electricity mix and is rapidly expanding. But Polis, with his Heat Beneath Our Feet initiative, seems hellbent on rectifying Colorado’s lack of geothermal street cred by backing Vail’s foray into the nascent form or ancient energy and an Eagle County project in Eagle as well.

Eagle County Commissioner Matt Scherr, while he would like to see far more leadership on climate change at the federal level, says it’s important to act locally, especially in a high-profile resort area such as Vail and surrounding Eagle County.

“This goes to that argument of what does it matter if Eagle County meets its climate goals [because this is] a global goal?” Scherr says. “I’m like, yeah, but don’t make me tell that starfish on the beach story. We are a community that is, particularly from a global perspective, really well resourced when it comes to money, when it comes to infrastructure. Some have called it a new energy economy focusing on the energy component of it, which is core. Then we will be the ones who have led the way and will be best positioned in that economy. There’s at least that opportunity.”

David O. Williams

Latest posts by David O. Williams (see all)

- The O. Zone: Strong storms incoming, Shiffrin GS PTSD, Powder to the People - February 10, 2025

- Union organizer calls paying patrollers in powder ‘economically ignorant’ in Colorado - February 7, 2025

- Democratization or ruination? A deep dive on impacts of multi-resort ski passes on ski towns like Vail - February 6, 2025